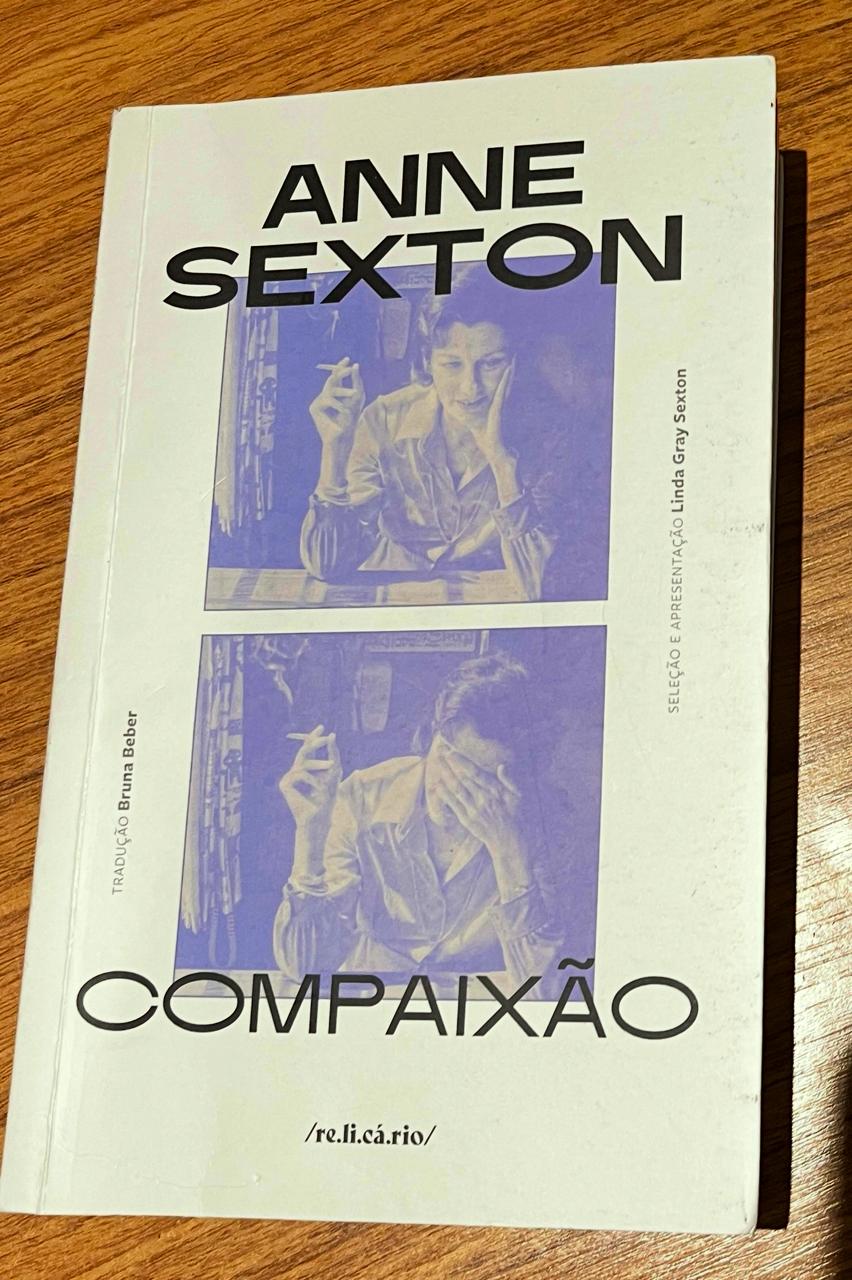

Três poemas de Anne Sexton

Do livro Compaixão, coletânea organizada por Linda Sexton com tradução de Bruna Beber

POEMADECIMA EDIÇÃO

1/6/20265 min read

Bruxaria

A mulher que escreve sente demais, tantos transes e presságios!

Até parece que ciclos e crianças e ilhas não bastam;

ou que chorões e fofocas e vegetais nunca bastaram.

Ela acha que pode prevenir as estrelas.

Uma escritora é sobretudo uma espiã.

Meu bem, eu sou dessas.

O homem que escreve sabe demais, tantos feitiços e fetiches!

Até parece que ereções e congressos e resultados não bastam;

ou que máquinas e galeões e guerras nunca bastaram.

Da mobília velha ele faz uma árvore.

Um escritor é sobretudo um patife.

Meu bem, você é desses.

Nunca o amor-próprio,

odiamos até nossos sapatos e chapéus,

mas nós nos amamos, querido, querida.

Nossas mãos de um azul suave e meigo.

Nossos olhos repletos de confissões hostis.

Mas quando resolvemos viver em harmonia

as crianças saem de casa enojadas.

É a despensa lotada e não sobra ninguém

para se empanturrar dessa abundância esquisita.

The Black Art

A woman who writes feels too much, those trances and portents!

As if cycles and children and islands weren't

enough; as if mourners and gossips and vegetables

were never enough.

She thinks she can warn the stars.

A writer is essentially a spy.

Dear love, I am that girl.

A man who writes knows too much,

such spells and fetiches!

As if erections and congresses and products weren't enough;

as if machines and galleons and wars were never enough.

With used furniture he makes a tree.

A writer is essentially a crook.

Dear love, you are that man.

Never loving ourselves,

hating even our shoes and our hats, we love each

other, precious, precious.

Our hands are light blue and gentle.

Our eyes are full of terrible confessions.

But when we marry,

the children leave in disgust.

There is too much food and

no one left over to eat

up all the weird abundance.

pré-escrito

Terra, Terra,

girando em seu carrossel

rumo à extinção,

retorna às raízes,

engrossando o molho dos oceanos,

apodrecendo cavernas,

você está virando latrina.

Suas árvores são cadeiras equivocadas.

Suas flores gemem na frente do espelho

e clamam por um sol que não usa máscara.

Suas nuvens vestem branco,

tentando virar freiras e fazem novenas aos céus.

O céu está amarelo de icterícia,

e suas veias desaguam nos rios

onde peixes ajoelhados

engolem cabelos e olhos de cabra.

De modo geral, eu diria

que o mundo está enforcado.

E, quando me deito na cama à noite,

ouço meus vinte sapatos conversando sobre isso.

E a lua, sob o capuz sombrio,

cai do céu toda noite

e abre sua bocarra vermelha

para chupar minhas cicatrizes.

Remadura

Uma história, uma história!

(Deixa estar. Deixa faltar.)

A este mundo cheguei prejudicada

como um para-choque Plymouth.

Primeiro o berço com seus ferros glaciais.

Depois as bonecas

e a devoção às bocas de plástico.

Aí veio a escola,

fileirinhas de cadeiras arrumadas,

maculando meu nome sem parar,

mas submersa todo o tempo,

uma estranha de cotovelos imprestáveis.

Depois a vida

com seus abrigos cruéis e pessoas

que mal se encostavam -

e o toque é fundamental -

mas eu cresci,

feito um porco de sobretudo eu cresci,

e aí vieram aquelas aparições esquisitas,

a chuva insistente,

o sol virando peçonha e por aí vai, serras

averiguando meu coração, mas eu cresci, cresci,

e Deus estava lá feito uma ilha para a qual não

remei, ainda ignorante Dele, braços e pernas

ajudaram, e eu cresci, cresci,

usei rubis e comprei

tomates e agora, na metade da vida,

digamos uns dezenove anos nas costas,

estou remando, remando

apesar do grude e da ferrugem das forquilhas e do

mar que pestaneja e encrespa feito globo ocular

injetado, sigo remando, remando,

embora o vento me empurre para trás

e eu saiba que aquela ilha não será ideal,

que terá os defeitos da vida,

os absurdos de uma mesa de jantar,

mas haverá uma porta eu a abrirei

e me livrarei do rato que carrego em mim, um roedor pestilento.

Deus o pegará com as duas mãos e o abraçará.

Como se diz em África:

essa é a história que acabei de contar, se foi boa,

se não foi boa, passe adiante para que volte para mim.

Essa história termina comigo ainda remando.

Rowing

A story, a story!

(Let it go. Let it come.)

I was stamped out like

a Plymouth fender into this world.

First came the crib with its glacial bars.

Then dolls

and the devotion to their plastic mouths.

Then there was school,

the little straight rows of chairs,

blotting my name over and over,

but undersea all the time,

a stranger whose elbows wouldn't work.

Then there was life with its cruel houses

and people who seldom touched -

though touch is all - but l grew,

like a pig in a trenchcoat I grew,

and then there were many strange apparitions,

the nagging rain, the sun turning into poison and all of that, saws working through my heart,

but I grew, I grew,

and God was there like an island

I had not rowed to,

still ignorant of Him, my arms and my legs worked,

and i grew, 1 grew,

I wore rubies and bought tomatoes

and now, in my middle age, about nineteen

in the head I'd say, Tam rowing, 1 am rowing

though the oarlocks stick and are rusty and the sea

blinks and roils like a worried eyeball,

but Iam rowing, I am rowing, though the wind

pushes me back it will have the flaws of life,

and I know that that island will not be perfect,

the absurdities of the dinner table,

but there will be a door and I will open it

and I will get rid of the rat inside of me,

the gnawing pestilential rat.

God will take it with his two hands and embrace it.

As the African says:

This is my tale which I have told,

if it be sweet, if it be not sweet,

take somewhere else and let some return to me.

This story ends with me still rowing.

As It was Written

Earth, earth,

riding your merry-go-round

toward extinction,

right to the roots,

thickening the oceans like gravy,

festering in your caves,

you are becoming a latrine.

Your trees are twisted chairs.

Your flowers moan at their mirrors,

and cry for a sun that doesn't wear a mask.

Your clouds wear white,

trying to become nuns and

say novenas to the sky.

The sky is yellow with its jaundice,

and its veins spill into the rivers

where the fish kneel

down to swallow hair and goat's eyes.

All in all, Id say,

the world is strangling.

And I, in my bed each night,

listen to my twenty shoes converse about it.

And the moon, under its dark hood,

falls out of the sky each night,

with its hungry red mouth

to suck at my scars.

Anne Sexton (1928–1974) foi uma poetisa norte-americana reconhecida por sua escrita confessional, marcada por temas como sofrimento psíquico, corpo feminino, maternidade, sexualidade, religião e morte. Nascida em Newton, Massachusetts, passou por longos períodos de depressão e recebeu diagnóstico de transtornos mentais ainda jovem. Durante uma crise, seu terapeuta a incentivou a escrever poesia como forma de terapia — foi aí que sua carreira literária começou.

Sexton estudou poesia com Robert Lowell e formou laços com outras poetas confessionais, como Sylvia Plath. Sua escrita direta, intensa e autobiográfica rompeu tabus e deu voz a experiências íntimas das mulheres em uma época em que esses temas raramente apareciam na literatura.

Seu primeiro livro, “To Bedlam and Part Way Back” (1960), chamou atenção da crítica. Em 1966, venceu o Prêmio Pulitzer de Poesia com “Live or Die”, obra que aborda sua luta contra a doença mental e a presença constante da morte. Outras obras importantes incluem “All My Pretty Ones” (1962) e “Transformations” (1971) — este último uma releitura sombria de contos de fadas.

Apesar do reconhecimento literário, Anne Sexton continuou enfrentando graves crises emocionais. Em 1974, morreu por suicídio. Após sua morte, surgiram debates sobre sua vida pessoal e ética de suas publicações póstumas, mas sua relevância literária permaneceu.

Hoje, Anne Sexton é considerada uma das vozes centrais da poesia confessional do século XX, influenciando gerações de escritores e ampliando os limites do que a poesia poderia expressar sobre o íntimo e o humano.